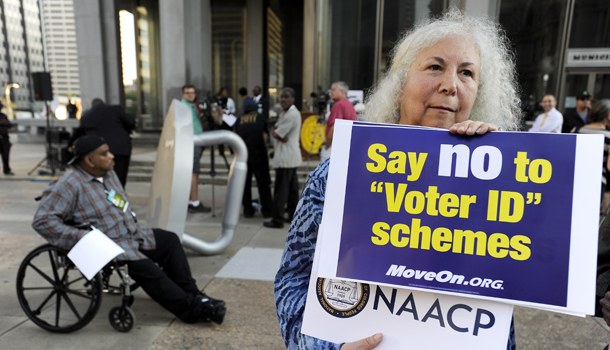

WASHINGTON — South Carolina is in federal court arguing that its new law requiring people prove their identity at the polls won’t make voting so tough that it reduces turnout of African-Americans, Hispanics and other minorities.

A federal panel is to determine whether South Carolina’s voter identification law violates the Voting Rights Act by putting heavy burdens on minorities who don’t have the identification. Last December, the Justice Department refused to allow South Carolina to require the photo IDs, saying doing so would reverse the voting gains of the states’ minorities.

Closing arguments in the case — which went to trial in August and included several state officials as witnesses — were scheduled for Monday. South Carolina has said it would implement the law immediately if the three-judge panel upholds it, although a decision either way is likely to be appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

Tougher state voter registration and identification laws could factor into this year’s election as voters divide along racial lines behind President Barack Obama or GOP nominee Mitt Romney in the presidential contest. About 90 percent of African-Americans and some 64 percent of Hispanic registered voters support Obama, according to the most recent Gallup three-week tracking poll. (Aug 20-Sept. 9). Democrats worry the ID laws may rob Obama and Democratic candidates of votes.

The law allows voters to show a driver’s license or other photo ID issued by the Department of Motor Vehicles, passport, military ID with photo or a voter registration card that includes a photo.

The law’s route to passage — after other versions failed in the 2009 and 2010 legislative sessions — was marked by bitter partisan and intra-party fights. Attempts at compromise by including additional acceptable identification and early voting days imploded. The 2009 House bill triggered a walkout by all but one African-American in the South Carolina House and the 2010 bill died in a filibuster by Senate Democrats.

Republican Gov. Nikki Haley signed the law in May 2011.

In his opening statement at trial, attorney for South Carolina Christopher Bartolomucci said the law was not a direct response to the 2008 record minority turnout that helped put Obama win the White House.

State witnesses said they wanted to instill public confidence in the election system and curb fraud, although they were unable to turn up instances of impersonation fraud that photo ID laws are designed to thwart. ButSouth Carolina lawmakers testified the law would also act as a deterrent to other types of fraud.

South Carolina’s population is 64 percent white, 28 percent African-American and 5 percent Hispanic. State election data produced in the trial showed some 178,000 registered voters did not have DMV-issued identification. Of those, 30 percent were white and 36 percent were minority voters. The data did not show if they had the other accepted IDs.

The judges in the case honed in on part of the law allowing voters without the required identification to cast a provisional ballot. But they must sign a statement that says they had a “reasonable impediment” preventing them from obtaining one of the required IDs. The affidavit would have to be notarized.

Marci Andino, South Carolina’s State Election Commission executive director, testified poll workers would be encouraged to err on the side of voters in deciding whether the potential voter truly had a “reasonable impediment.” Notaries at the 2,100 polling locations would not charge fees, she said. If a notary was not available, affidavits would be accepted anyway, Andino said.

The U.S. Supreme Court has previously upheld Georgia and Indiana voter photo identification laws, whichSouth Carolina officials said served as models and guidance for their law. But those state laws allow voters to show more forms of identification.

Attorneys for the Justice Department and opponents have argued the provision’s definition of what qualifies as a reasonable impediment is vague and could be applied differently from county to county. Opponents raised enough questions that South Carolina Attorney General Glen Wilson was compelled to clarify before the trial ended how the law would work.

The judges on the panel hearing the South Carolina case are Colleen Kollar-Kotelly and John D. Bates of the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia and Brett M. Kavanaugh of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Kollar-Kotelly was appointed by former President Bill Clinton. Bates and Kavanaugh were appointed by former President George W. Bush.

— Associated Press